Acoustic Tagging and the Annual Herring Run

MIT Sea Grant and the MA Division of Marine Fisheries look below the surface as 600,000 river herring arrive in the Mystic River system for the annual spawning migration.

By mid-May, aquatic diving birds called cormorants had begun aggregating around the fish ladder by the Upper Mystic Lakes Dam in Medford, MA. A great blue heron stalked the shallows by a stream entrance, and two bald eagles perched nearby, tracking fish from above. MIT Sea Grant Assistant Director and Research Coordinator Robert Vincent, on location to track these same fish, recognized the birds’ behavior as an indicator that the annual river herring run was underway.

The Mystic River Watershed Association and the MA Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) estimate that over 600,000 river herring, both blueback and alewife, are currently migrating up the river to lay eggs. The presence of river herring, and in such large numbers, is a positive indicator of river health. The adult spawning migration monitoring season extends from April through early June when the river herring make their way from the Gulf of Maine into Boston Harbor, and on to their freshwater journey up the Mystic River into the lakes and ponds to spawn. Each female river herring is expected to lay 60,000-100,000 eggs. But what else is going on below the surface once they arrive?

Working with Marine Fisheries Biologist Benjamin Gahagan from the MA DMF and Assistant Professor of Fish Population Ecology and Conservation Adrian Jordaan from the University of Massachusetts Amherst , Vincent and the monitoring team are turning to acoustic tagging and telemetry tracking to inform this question.

Expanding on their ongoing efforts to assess habitat preferences and resource use in spawning ponds with man-made fish passage structures like fish ladders and step dams, the team aims to gain a better understanding of the locations preferred by spawning river herring once they arrive in the interconnected waterways.

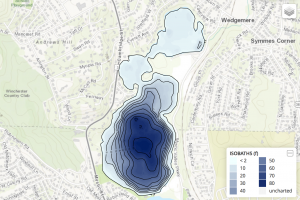

In January, MIT Sea Grant created a bathymetric map of Upper Mystic Lake using data provided by the MA DMF. The monitoring team used the map to determine best placement for 23 acoustic monitoring receivers at stream entrances and up or downstream from fish passage structures in Earhart Locks, Upper and Lower Mystic Lakes, Central Falls and Wedge Pond, and Horn Pond. The VEMCO VR2W receivers will receive a ping documenting location, date, time, and tag number when a fish with an acoustic tag swims by. These data will help shed light on river herring movement throughout the system, and the effect of fish ladders or step dams on passage. This pilot study will identify areas of the Mystic River system where fish are spending most of their time, and will inform larger study designs that will focus effort on where the fish occur and avoid areas where fish are not observed, saving time and resources.

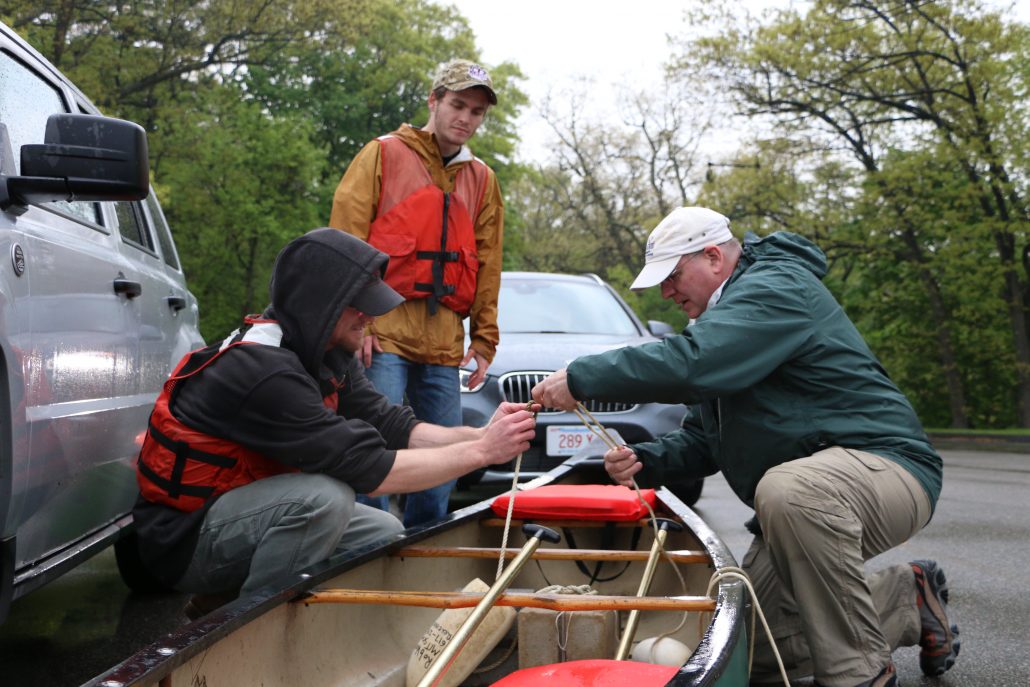

At last, the water temperature had risen to 51 degrees F, triggering the annual river herring migration. On May 17, Vincent eyed the orange radar cluster on his phone screen, indicating near-constant rain at the Upper Mystic Lake in Medford, MA. The precipitation was no problem for the fish, so the eight-person team packed underneath an eight by eight-foot pop-up tent, and the work proceeded.

In addition to the representatives from MIT Sea Grant and the MA DMF, five students joined the tagging efforts, including Meaghan Rafferty, a graduate student in Environmental Studies at Antioch University who is working with Vincent at MIT Sea Grant. Dawson Bathgate and Pete Norwood, two students from the University of Massachusetts Amherst Natural Resource Conservation program, also pitched in.

First, the monitoring team hoisted buckets of river herring from the dam area and carried them to the netted holding pen they had set up in the shallow water. Under the pop-up tent, a 50-quart cooler acted as a staging tank, fitted with a PVC pipe cut lengthwise to serve as a half-submerged fish operating table. Gahagan measured the first adult herring, identified the sex, and prepared to implant the acoustic transmitter. Vincent recorded the data and corresponding VEMCO transmitter identification number as Gahagan made his incision through the belly to insert the jelly bean-sized transmitter.

In total, 31 fish surgeries were performed. Once the tagged fish were stitched up and placed in the holding tank, the team monitored their activity to ensure that they had recuperated before being released back into the lake.

River herring are important prey species for freshwater recreational fisheries, marine mammals and commercial fisheries, and terrestrial predators. Just like the cormorants, eagles and herons spotted waiting by the fish ladder for a meal, many other species depend on river herring as an important food source, including larger fish like bass and perch, otters, and even raccoons. River herring play a vital role in the Mystic River watershed food web, but they are also a key link in the transfer of nutrients found in marine environments into freshwater systems and back again, weaving a strong web to restore and maintain ecosystem connectivity.

By assessing the movement of spawning adult river herring in the Mystic River system, this pilot study will inform the Division of Marine Resources with regards to management of spawning populations, as well as identify specific locations for focusing larger river herring monitoring efforts to better understand our annual visitors. The Massachusetts Bays National Estuary Program (MassBays) provided funding in support of this project, and the work will help inform the MassBays priority embayments program (MassBays National Estuary Program, EPA Grant No. CE96173901). Additional support from this work was provided by the Woods Hole Research Center.

Read more about the Mystic River Watershed, from its history, to water quality and recreation >>

Learn more about River Herring monitoring with the Mystic River Watershed Association >>